January opens with the Feast of St Basil and closes with the Feast of the Three Hierarchs, the three most outstanding ecumenical teachers of the Holy Trinity and champions of Orthodoxy. These pillars of the Church are so multifaceted that it is hard to know where to begin: should we discuss their advocacy for justice in civil society? Their sponsoring of hospitals and care for the poor? Their patronage of secular letters, and the reasons they gave for the edifying use and preservation of pagan Greek literature, from Homer to Plutarch? After all, in Greece they are celebrated as the finest patrons and paradigms of Greek learning. Or are we to turn to their mystical side, their prayerful union with God? Their life as monastics and ascetics?

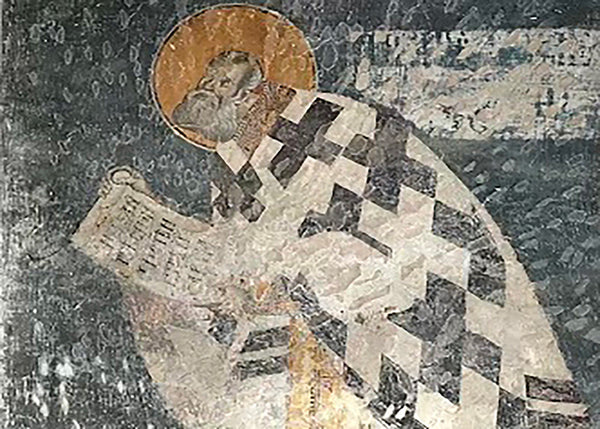

It seems to me that the best approach, which encompasses a little bit of each of these facets, is provided by our own church iconography. Now, the icon most familiar to us shows them standing side-by-side with each other, invested with equal authority. But there is another depiction, hidden in countless frescoes behind the altar, where we see them serving as archpriests at the altar of the Lord. Their stance is one of supplication and offering, as they hold up their scrolls as sacrifices to God.

St Gregory the Theologian, in turn, provides an excellent verbal explanation for interpreting this icon: the purpose of human beings is to return to the Word, as an image to its archetype. Being made in the image of God the Word, we are rational creatures with the unique gift of speech, language, and understanding. Thus, as St Gregory so often puts it, he offers up his words (logoi) in gratitude to God the Word (Logos). They are a ‘living sacrifice’, an offering of the ‘rational worship’ (logike latreia) (Rom 12:1) that is most befitting to the human race.

Gregory expresses this in a moving Paschal hymn to Christ:

It is worthy noting that St Gregory addressed this hymn to Christ after breaking a long period of complete silence. His properties he dedicated to Christ. His silence he dedicated also. Now he has nothing left to give him but these words of praise. This is an excellent illustration of how the words of the Fathers are the fruits of deep contemplation, stillness, and silence. The reason he broke his silence was to give an example of whole-hearted offering to Christ, inspiring us to do likewise.

Gregory’s understanding of rational worship helps us to understand how, even when we meditate on the words of the Church Fathers in private study, we are still participating in the liturgical life of the Church. On the other hand, when we pray, chant, and serve in the Church of God, we see their words being embodied in the liturgy. Our body becomes a living sacrifice and an offering of rational worship. Thus, the life of private and common prayer complement and reinforce each other. That was the kind of prayer that the Church Fathers exemplified in their own lives.

In his orations for feast-days of the Church, St Gregory comes to us as the “chief of the feast” (o tēs eortēs exarchos Or. 39.14), the liturgical toastmaster. For him the feasts of the Church are not just commemorations of historical events, but acts of cosmic worship. At the feast of the Nativity, he points out how we follow the celestial bodies that Christ set in motion at the beginning of time: “We ran with the star, and venerated Him with the Magi.” The purpose of the feasts, too, is to lift up the humble to join in the chorus of the ‘heavenly minds’ on high: “We were surrounded by light with the shepherds, and glorified Him with the angels.” Yet nothing surpasses the inscrutable mystery of partaking of Christ Himself, as we do in Baptism and the Eucharist: “Christ is illumined, let us shine with Him. Christ is baptized, let us descend with Him, that we may also rise together with Him (ibid).”

☩

As for St Gregory’s dear friend St Basil, and his later successor to the archepiscopal throne of Constantinople, St John Chrysostom, there is no need to dig deep to discover their liturgical significance. The liturgies of St Basil and St John Chrysostom are the two most commonly celebrated liturgies in the Orthodox Church (with the exception of the Presanctified Liturgy of St Gregory the Dialogist, Pope of Rome).

Although the liturgy of St Basil is similar to St John Chrysostom’s, it is lengthened by longer priestly prayers, most notably the anaphora, the prayer of ‘offering up’ and thanksgiving. The anaphora culminates in the epiclēsis, where the priest calls on the Father to send down the Holy Spirit to make the bread and wine the very body and blood of Christ. Nevertheless, because these prayers are often said silently, many attendees are not aware of any difference, perhaps only noticing that the Sunday liturgies during Lent take longer than usual.

Let us take a quick look at some of the beautiful passages in St Basil’s anaphora, which is a summary of salvation history, of the Gospel itself. In fact, within the text of the anaphora Basil even explains how liturgy works by the grace of the Holy Spirit. The soul naturally desires to worship God, the One Who Is (o On) (Ex. 3:14), out of gratitude that He is, and that He has brought all existence into being, and for showing the Truth, which is simply the knowledge of being. It is worthy for us “to offer Thee this our rational worship (logikē latreia), for Thou hast given us the knowledge of Thy truth.” The Holy Spirit is “the source of holiness, by which all creation, rational and noetic, is empowered and worships Thee, and sends up eternal praise to Thee, for all things are Thy servants.” At this point Basil also mentions the nine ranks of angels we discussed in our last articles: “For Thou art praised by Angels, Archangels, Thrones, Dominions, Powers, Authorities, Virtues, and the many-eyes Cherubim, around Thee stand the Seraphim.” And this is only the first part of the anaphora. By celebrating it during the period of Lent, we are annually reminded of the theological depths of the Divine Liturgy.

In addition to Basil’s position as bishop of Caesarea and champion of Orthodoxy, he was arguably the single most important monastic reformer in the history of Eastern Orthodox monasticism. One reason why Basil’s contribution was so vital is because it reconciled two opposing tendencies in monasticism. As Gregory puts it in his Funeral Oration for his friend, Basil managed to unite the solitary/contemplative and the common/active monastic life:

These had been in many respects at variance and dissension, while neither of them was in absolute and unalloyed possession of good or evil: the one being more calm and settled, tending to union with God, yet not free from pride, inasmuch as its virtue lies beyond the means of testing or comparison; the other, which is of more practical service, being not free from the tendency to turbulence. He founded cells for ascetics and hermits, but at no great distance from his cenobitic communities, and, instead of distinguishing and separating the one from the other as if by some intervening wall, he brought them together and united them, in order that the contemplative spirit might not be cut off from society, nor the active life be uninfluenced by the contemplative, but that, like sea and land, by an interchange of their several gifts, they might unite in promoting the one object, the glory of God (Funeral Oration for St Basil, Or. 43.62).

Reading this closely, it almost sounds like a poetic description of Mt Athos, which likewise combines sea and land, as well as the communal life of cenobitic monasteries with the solitary life of scetes. That is no coincidence, for St Basil truly is the architect of Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

☩

We all know St John Chrysostom as the author of the Divine Liturgy named after him. And it is through the Liturgy of the Word, too, that St John earned his epithet Chrysostom, “golden-mouthed,” since he preached on the scripture readings throughout the liturgical year. In many respects, the cycles of readings are the same today as they were in his own time, as we can see from St John’s cycle of homilies on Genesis during Lent, or his homilies on the Acts of the Apostles after Pascha). It is easy to compliment our daily scriptural readings with Chrysostom’s commentary, as so many monasteries do in their refectory readings. There is also a useful app called Catena, available on Apple and Google Play, which gives readings from both the Greek and Coptic Lectionary and verse-by-verse commentary by the Church Fathers.

As for the Liturgy of the Faithful, Chrysostom, in addition to serving at the altar and distributing the bread of life, he was ever eager to instruct Christians on how to extend the liturgy practically into their own lives. Chrysostom explains how every Christian home can become a ‘little church’. The self-sacrifice of Christ commemorated is in fact a model for hospitality and charity in every household.

The Church has ordained a specific order of priests to serve at the altar. Chrysostom maintains a very strict standard for this order of bishops and priests. But he also makes it clear that our ministry to the poor is nothing less than the “royal priesthood” that belongs to every Orthodox Christian. Only few are called to serve at the altar, but all are called to serve as priests of charity, serving Christ at the altar of our neighbor’s needs.

St Paul had implied much the same when describing the ministry to the poor as a liturgical thanksgiving offering: “The ministry of this service (leitourgia) not only fills up the measure of the needs of the saints [faithful], but also abounds through many thanksgivings (eucharistiai) to God'' (2 Cor 9:12-14). In English translation, the liturgical and eucharistic overtones of this passage are almost entirely lost. But leave it to Chrysostom to make you feel the full weight of this liturgy of mercy. Commenting on Paul’s exhortations to charity and almsgiving, John makes a bold comparison of the altar he serves at with the altar of mercy that all Christians must serve:

That altar [of mercy] is made of the very members of Christ, and it is the body of the Lord that is made your altar. Revere it then; it is upon the flesh of the Lord that you offer the sacrifice. That altar is even more awesome than this which we now use [in church], not only than the one used of old [in Israel].

Do not balk at what I am saying. For this altar is venerable because of the sacrifice that is laid upon it: but that altar of mercy, not only because of that, but also because it is made of the very sacrifice which makes the other altar venerable. Again, this altar is only a stone by nature, but becomes holy because it receives Christ's Body: but that altar is holy because it is itself Christ's Body. So that altar which you, the layperson, stand next to, is more awesome than this one.

Chrysostom is here trying to resolve the ‘cognitive dissonance’ that many Christians are susceptible to, if not outright hypocrisy. “Indeed you honor this altar because it receives Christ's body; yet you treat with contempt [the poor man] who is himself the body of Christ, and neglect him as he perishes! (Homilies on 2 Corinthians, 20.3).” They may reverence the altar of the Church, but they don’t seem to be able to make the connection between the sacrifice done in Church and the sacrifice they must do on their part through charitable giving. The altar of mercy is present everywhere, amidst the poor, whom, as Christ says, “you will always have with you,” as an icon of Himself (Mt. 26:11, Mt 25:34-40). If we were living truly liturgically, we would be serving at the altar of mercy constantly. We would be aware of the power of the Liturgy to sanctify our service and work, turning all our deeds of love into a prayerful invocation of the Holy Spirit.

That altar you can see lying everywhere, both in streets and in market-places, and you can sacrifice upon it at every hour; for sacrifice is performed there as well. And just as the priest stands invoking the Spirit, so do you also invoke the Spirit, not by speech, but by deeds. (ibid.)

Theologians like to call this “the liturgy after the liturgy”. It is the living, continuous extension of the Liturgy into our lives, through deeds of loving-kindness, almsgiving, and hospitality.

Even when we are poor and feel as though our contribution is too small, St John suggests we save up little by little, storing pennies like so many widow’s mites, “For now, save up at home, and so make your house a church; your little box, a treasury. Become a guardian of sacred wealth, a self-ordained steward of the poor. Charity (philanthropia) bestows upon you this priesthood.”

(Homilies on 1 Corinthians 43.1).

Here, St John is far from disparaging the ministry of deacons, priests, and bishops specially ordained for preaching the Gospel and administering the sacraments. What he is doing here is showing the organic manner in which the Divine Liturgy, celebrated by the ordained priesthood, is extended into the lives of the faithful, so that all may participate in a unified liturgy of sacrifice, prayer, and service. Christ’s sacrifice once and for all on the cross overflows into the Divine Liturgy, which then overflows into the good works performed by each of us. That is how God’s grace cascades to all creation from on high.

It is no chance that in almost every Byzantine Church with painted frescoes behind the altar, it is the Three Hierarchs who are depicted, often seen serving the timeless liturgy alongside other Church Fathers, such as St Athanasios and St Cyril, whom we celebrate in January. Let us take their words to heart and follow them as they lead us in the unceasing Liturgy before the throne of God, whether it be in a majestic cathedral, a humble mission parish, or in our own town’s streets and market-places.

2 comments

Interesting article, thank you for sharing

Thanks for these timely words. Hoky Three Hierarchs pray to God for us.

Leave a comment